When coordination pays off

We often talk about the costs of coordination and the benefits of decoupling. "Amazon is so fast because their teams don't have to coordinate". Convincing others to do something always takes longer than simply doing it.

But sometimes, coordination brings huge benefits and is totally worth it. Here is a story where upfront coordination was costly but yielded a much better outcome eventually.

Stripe background: Charges → Payment Intents

The US has a few different payment methods: cash, credit and debit cards, ACH debits and transfers, wires, etc. Merchants would integrate Stripe and charge their customers in the US. But each country has their own set of payment methods (e.g. Mexico has OXXO). So, when those merchants wanted to sell overseas they would have to do a different integration for the new payment methods in that region.

To solve this, Stripe made a new API, Payment Intents, meant to cover all payment methods. All merchants could integrate to this API once and then sell in all markets. Michelle Bu, lead Payment Intent designer, covers Payment Intent's arc in great detail here.

By trying to cover all global payment methods, Payment Intents is not the most convenient API for any given payment method. In particular, Payment Intents is not the most convenient for cards, the most popular payment method in North America, at the time Stripe's biggest market by far.

Not only did Stripe launch Payment Intents, it made it the one and only payments API.

In my view, Stripe was making the API less convenient for its biggest market. I pushed back against Payment Intents as the single payments API but I was overruled1. Payment Intents was it and if you wanted to offer more payments functionality, you had to work with it somehow.

The entire Stripe product team had to coordinate around Payment Intents. For example, when making a new version of Checkout (2018-2019), that team had to use Payment Intents as much as possible. You can configure the checkout page with the Checkout Session object but the payment itself is tracked by a Payment Intent.

Eventually, I accepted the decision and got to work: we replaced Charges with Payment Intents throughout the documentation, redesigning the documentation in the process. But it still took me a couple of years to see how forcing the company to coordinate around Payment Intents was the right trade-off.

Coordinating new projects from the start

By mid-2020, there were a few projects around the company, all somehow related to an old Stripe feature, Remember Me. Remember Me when Stripe remembers your card details in one merchant (e.g. OpenAI) and then pre-fills them in a different merchant (e.g. Notion). This makes it easier to pay for the buyer and improves conversion rates for merchants. It is a great feature but it hadn’t been prioritized since its launch in 2014.

The projects, all started by different teams, were:

- Bring Remember Me to all the new checkout pages Stripe had made since 2014 (new Checkout, Web Elements, Mobile Elements, etc.)

- Extend Remember Me to non-card payment methods like bank accounts.

- Remember Me for Financial Connections, Stripe’s product to share your bank account transactions with an app, like you can do with Monarch.

These three projects had the same shape: “buyer has a log-in managed by Stripe, used in multiple merchants sites”. So we coordinated to have a common brand and system for all those features. We combined efforts into what became Link.

It would’ve been easier and faster to do these 3 projects separately. But we could see how, if we coordinated, all those features would reinforce each other eventually.

Coordinating externally around Payment Intents

Because all payments features go into Payment Intents, Link's payment features (1 and 2 in the list above) went into Payment Intents too. It was harder to integrate into an existing API than to make a new one. But, because all merchants had already integrated with Payment Intents already, once Link was in Payment Intents, it reached all merchants at once.

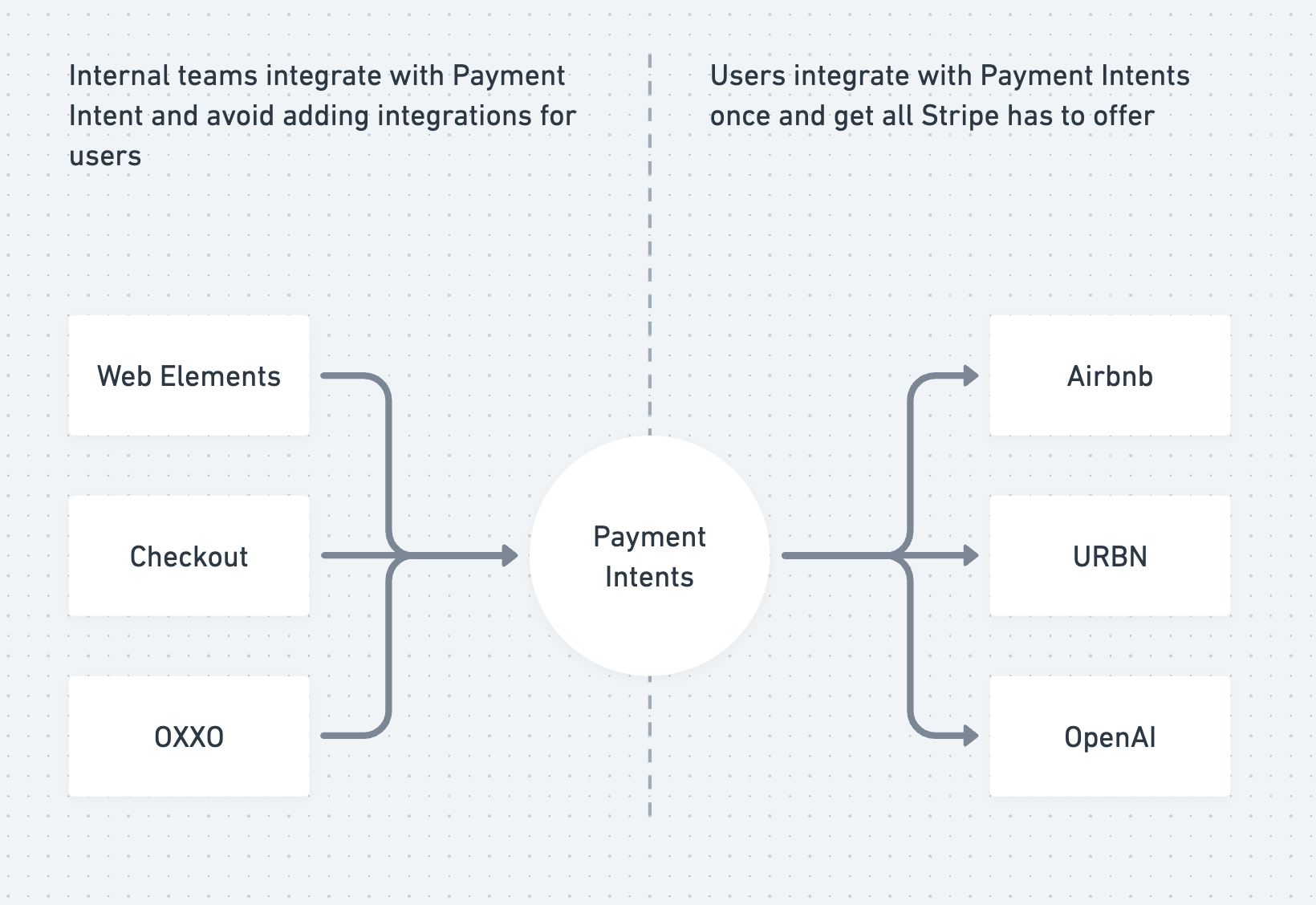

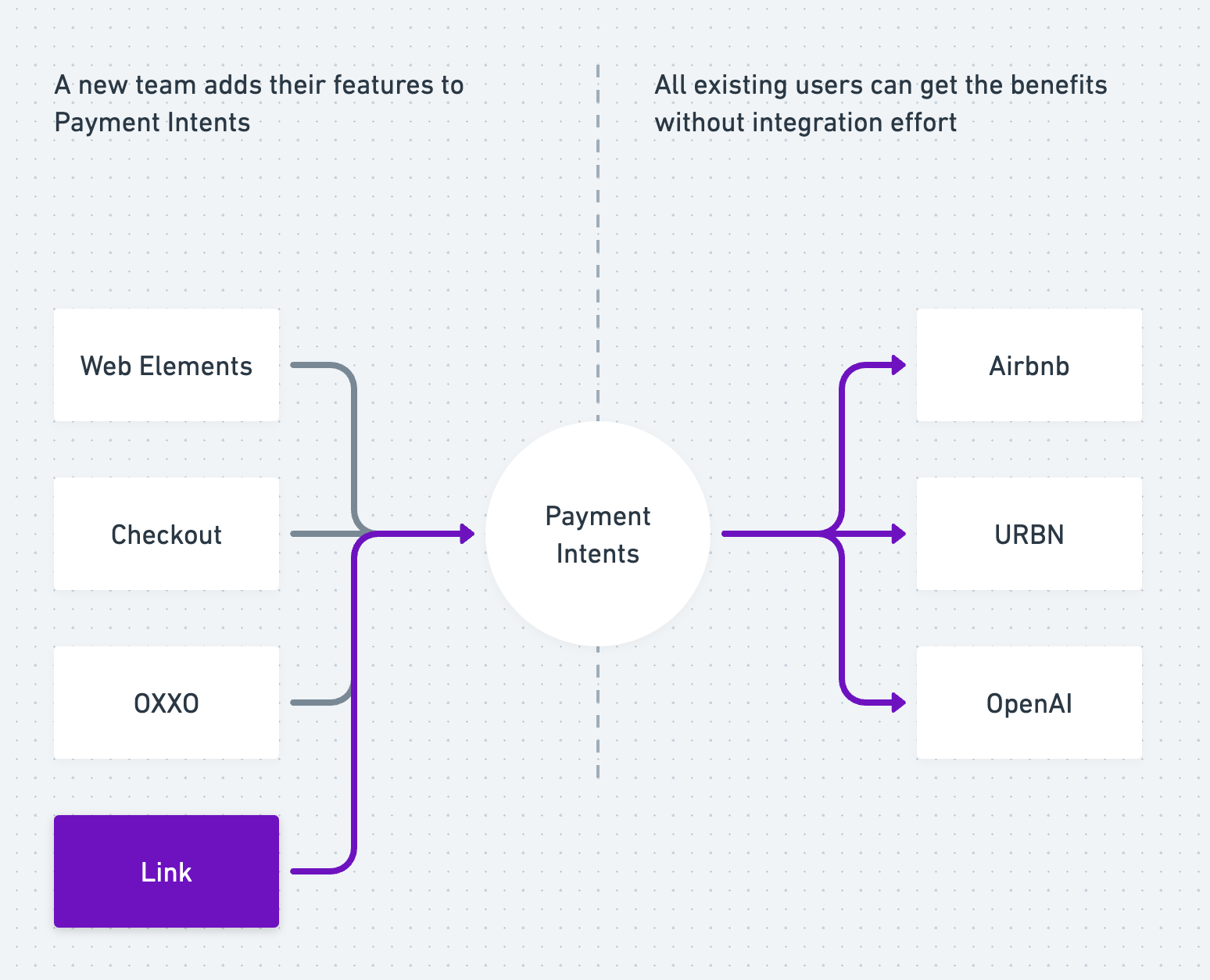

On the left side of this diagram, you have the internal Stripe teams exposing their features through one integration point, Payment Intents. On the right side, you have Stripe users, each with the same integration point.

This is great for merchants! They integrate once and they get all the Stripe payment features they want. As a Stripe user, this probably seems obvious to you. But when you are inside of a company, you see the world differently. Each team has their own goals and priorities; coordinating with other teams is a nightmare compared to working independently. You'd do anything to avoid that coordination and start building.

Coordinating internally around Payment Intents

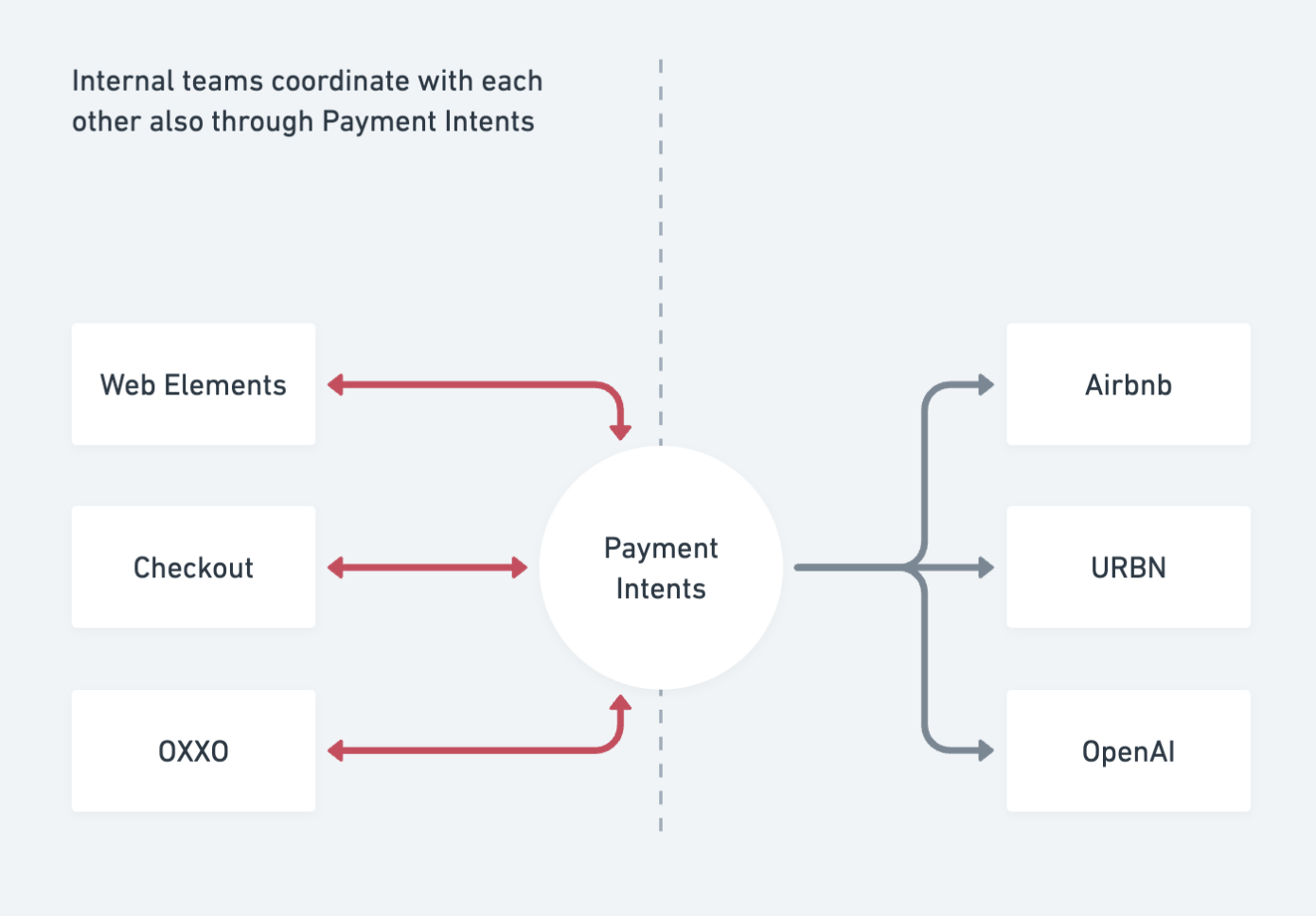

In practice, "Integrating Link in Payment Intents" meant "coordinating with many product teams at Stripe". For three months or so, we planned those internal integrations with the other teams. It felt like forever. But eventually, we collectively found the right design and implemented it. In many cases, it was the other team how did the bulk of the work. It took us a good chunk of 20212 to coordinate and implement all the internal integrations. At the time, it felt very slow.

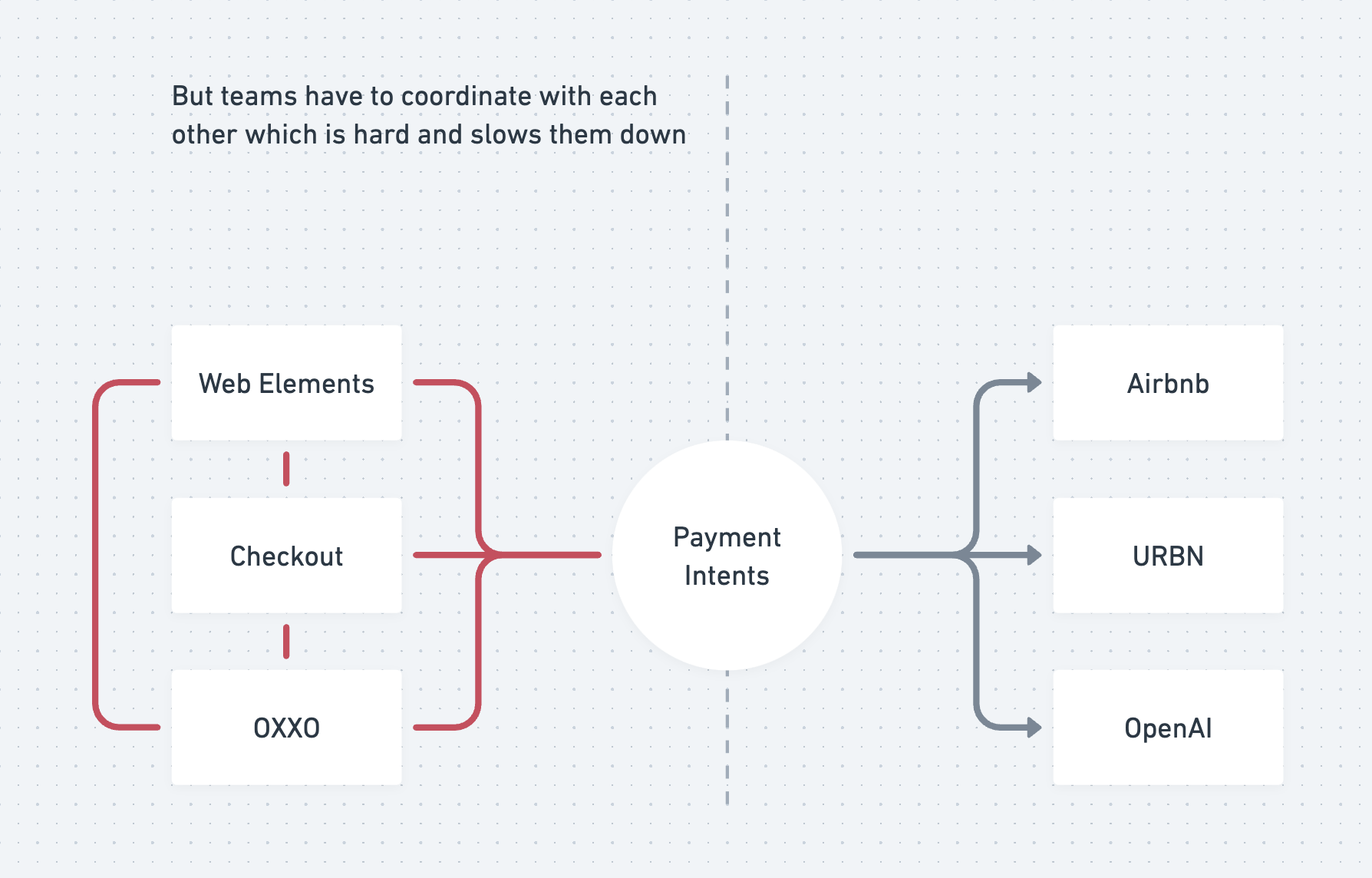

This is the same diagram as above, but with red arrows where the internal Stripe teams have to coordinate with each other. They represent the coordination cost we all dread.

But even there, may of these costs weren't that bad. For example, because the Checkout team had also integrated with Payment Intent, once we added Link to Payment Intents, we had partially added Link to the Checkout codebase. This would’ve been much harder if Checkout had its own data models.

This was also true for Web and Mobile Elements. Because every Stripe product is integrated with Payment Intents, once new products integrate with Payment Intents, they've integrated with everything else.

Coordinating through one model is not a panacea but it helped in this context.

The AWS way: decoupling

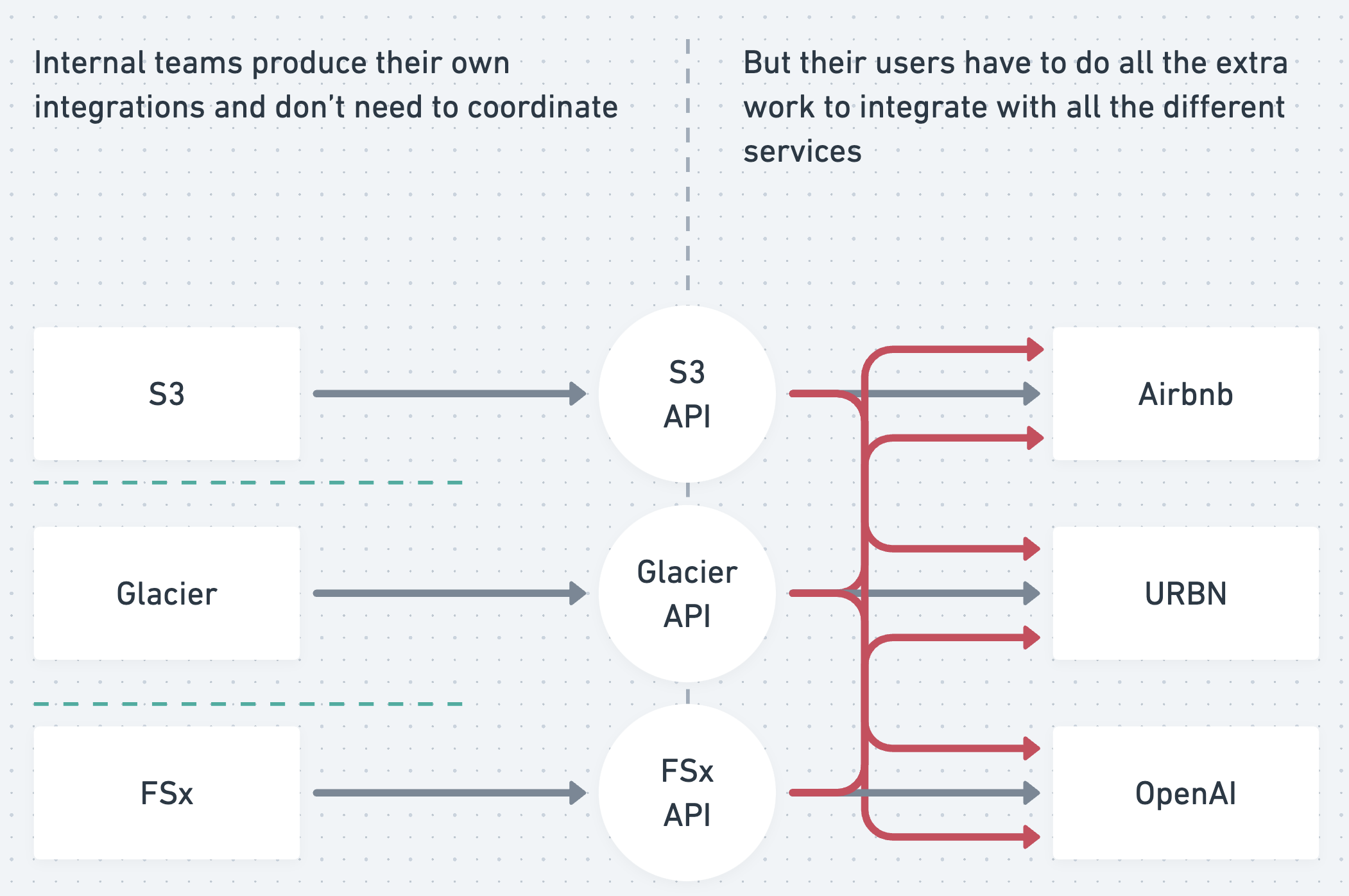

From the outside, it seems like AWS products decouple as much as they want. When they launched Glacier (cheaper S3 with higher latency), Glacier's first API was totally different to S3's despite the two products being "the same one on a different spectrum" from the user's perspective.

But from the Glacier's team perspective, the split API makes perfect sense: coordinating with the already contended S3 team will delay them by 6 months. It is much easier to make a custom API for Glacier. So they did.

But whatever time they saved in internal coordination costs, they passed on to their users. Now each user has to integrate twice, once for S3, once for Glacier. And if you add a third storage product, FSx3, then each user has to integrate three times to get all of them.

Notice how the coordination red arrows moved from inside the company (left side of the diagram) to outside the company (right side).

Eventually, Glacier integrated its functionality into the S3 API, which is now the recommended integration. They probably realized how much more usage Glacier would get if it was integrated to S3. And that made the coordination cost totally worth it.

I don't mean to imply that all of AWS should be one API. The shape of their services or breadth of use-cases make this obviously a bad idea. But the Glacier example is trying to show that at least some of the services have overlapping functionality that users would rather think about in the same API.

Reaping the rewards of coordination

Eventually, all that internal coordination paid off. Most merchants could turn on Link with no integration changes or by changing only a few lines of code. Stripe also recommended Link to all new users in the standard Payment Intents integration. We barely had to change the documentation to do that.

It also helped with enterprise. We wouldn't have closed half of our first deals if we had asked them to integrate with another API from scratch. And it would’ve taken us twice as long to close the rest of the deals. To merchants, the cost of integrating the API, measured in developer time, is often bigger than the cost of whatever Stripe is selling! Big merchants have dozens of dependencies on Stripe's API beyond the checkout form (refunds, disputes, reconciliation, counting fees, taxes, etc). If in each of those flows they needed to account for Link separately, Link would've gotten nowhere.

By adding Link to Payment Intents, we bypassed most of those costs.

The upfront coordination cost eventually translated into a constant tailwind for Link. As more merchants integrate with Payment Intents for any reason (e.g. Tax), they can get Link without additional integration costs. And when they integrate Payment Intents because of Link, then they can get every other feature (e.g. Tax) without additional costs. In this world where we coordinated, the number of Stripe product each merchant uses is much higher than in the alternative world where we didn't.

So, next time you are reluctant to coordinate (as I often am), consider the value of what you are getting in return!

Footnotes

- Once Payment Intents was chosen, we still wanted to make it more convenient for North American developers. With David Ackerman, we designed

error_on_requires_action=true, which makes Payment Intents work like Charges. In my opinion, it is the ugliest parameter in Payment Intents. But eventually, lots of US merchants used it to quickly migrate from Charges to Payment Intents with a one-to-one migration.↩ - I am simplifying the story. We shipped many different features throughout 2021. For example, Remember Me launched in new Checkout by early 2021. Then it made it to Web Elements, and then it made it to Mobile Elements. And it made it North American before it made it to Europe. But the basic story is the same: upfront coordination costs with delayed implementation and rewards.↩

- The real FSx doesn’t have the same shape as S3 and Glacier, I am using it as an illustration of “AWS will continue to put out storage APIs”.↩