The birth of a (pseudo) currency

A dozen pseudo-currencies were issued in Argentina in 2002. How did that work? And why are they coming back in 2024?

What is a pseudo-currency? How do they start? Why do they have value?

This post walks through that process in the most concrete way possible and hopefully shows that they are not that difference from "real" currencies. No Big Theory required.

Back to 2002

Imagine you are the government of a province in Argentina, like La Rioja. Your costs are ARS 2M per year, but your tax revenue is only ARS 1M per year. You get the missing ARS 1M from the federal government, which redistributes national taxes to each province. Your province happens to spend more pesos than it gets in tax revenue – you have a deficit that is covered by the federal government.Suddenly, the federal government stops the distributions. They did this because they had promise to only print pesos if they had dollar reserves to back them 1:11 and they run out of dollars. Regardless of why this happens, overnight, you the province are short ARS 1M to pay your costs. Many of those costs are salaries to your government workers and pensions.

End of the month comes and workers show up to get their salary. You don't have enough money to pay them. What can you do? You can refuse to pay them. Or you can invent something to pay them with.

You print some paper that says: "This is valid for one peso to whoever carries to be paid by the province"

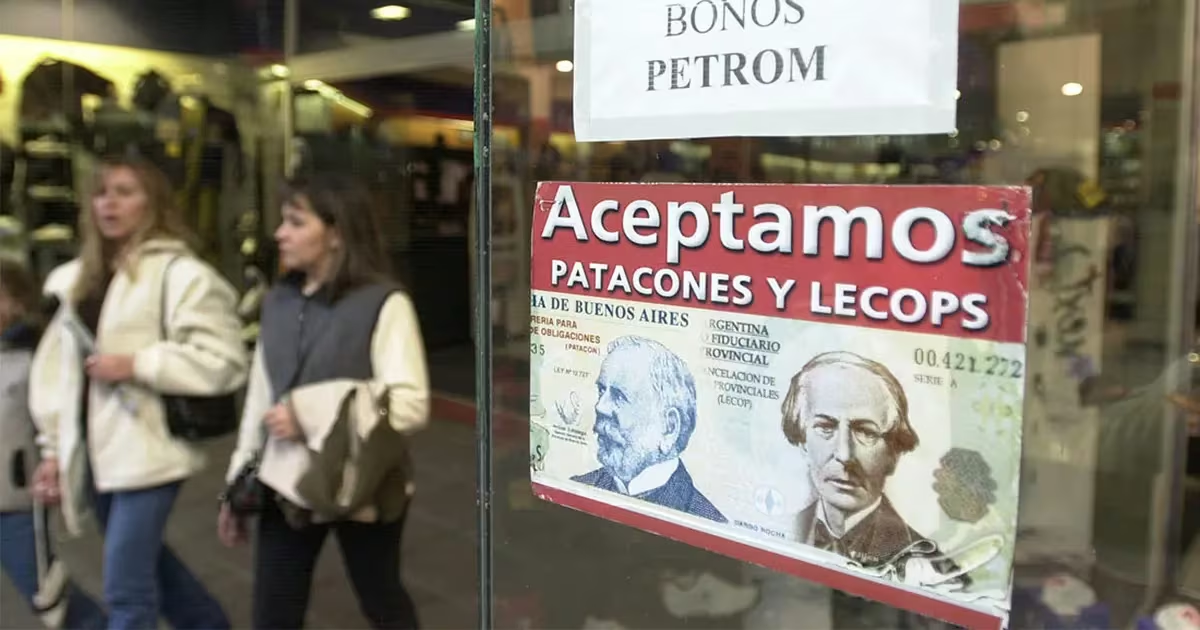

Here is a Bono Patacon, emitted by the province of Buenos Aires:

And here are some other designs from Buenos Aires and other provinces:

As a province you don't have the legal authority to issue "real" pesos. So, this is technically a bond but you hope people will accept it as pesos, because that is what people want.

You meet the angry workers who want to get paid:

You: I will pay half of your salary with the pesos I have and the other half with these bonds.

Them: What can are these good for? We want real money!

You: You can use them to pay taxes! I'll accept them instead of taxes2. Also, utilities like telecoms, electricity, and water will accept them as payment too.

The utilities are accepting the bonds because you forced them to.

The workers have no choice so they take what you give them, hoping they'll be able to spend these bonds somehow.

The workers go back home. On the way they want to buy some bread from the baker. The baker doesn't really want bonds but they also do they want to sell their bread and half of their customers are carrying bonds. So, the baker agrees to accept the bonds to sell bread. Because not everybody accepts them yet, they put a sign saying "We accept bonds!".

Your bond graduated into a pseudo-currency! It can be used to purchase things in most places.

Months go by and there are a lot of bonds circulating. Workers always try to pay first with the bonds, and only later with the relatively scarcer pesos. This is called Gresham's law: bad money drives out good money.

This results in the baker receiving more bonds than it needs to pay for taxes and utilities. When he tries to pay for flour with them, the supplier rejects it because he too has too many bonds. They negotiate and the supplier is willing to accept bonds at a 5% discount to pesos. So, if flour was ARS 100 per kilogram, the baker has to pay 105 bonds for it.

To reflect this, the baker sets a sign in their store "Bonds accepted at 0.95"3. The other bakers all have the same problem, so they do the same.

Your pseudo-currency now has an exchange rate, given by the "market". This is a very decentralized market with no clearing house. Instead, each gas station, grocery store, hair salon, etc decides how many bonds to accept and at what rate. But if anybody of them undervalues the bonds with respect to the market, their customers go to the competition.

This goes on until your provincial government or the federal government has enough pesos to exchange for the bonds. One way this can happen is when the federal government agrees to start printing pesos again. When you own the printer, everything is possible. Then, when the government starts trading pesos for bonds, everybody rushes to convert them, and they quickly disappear.

Your pseudo-currency doesn't exist anymore.

2024, Back to the future

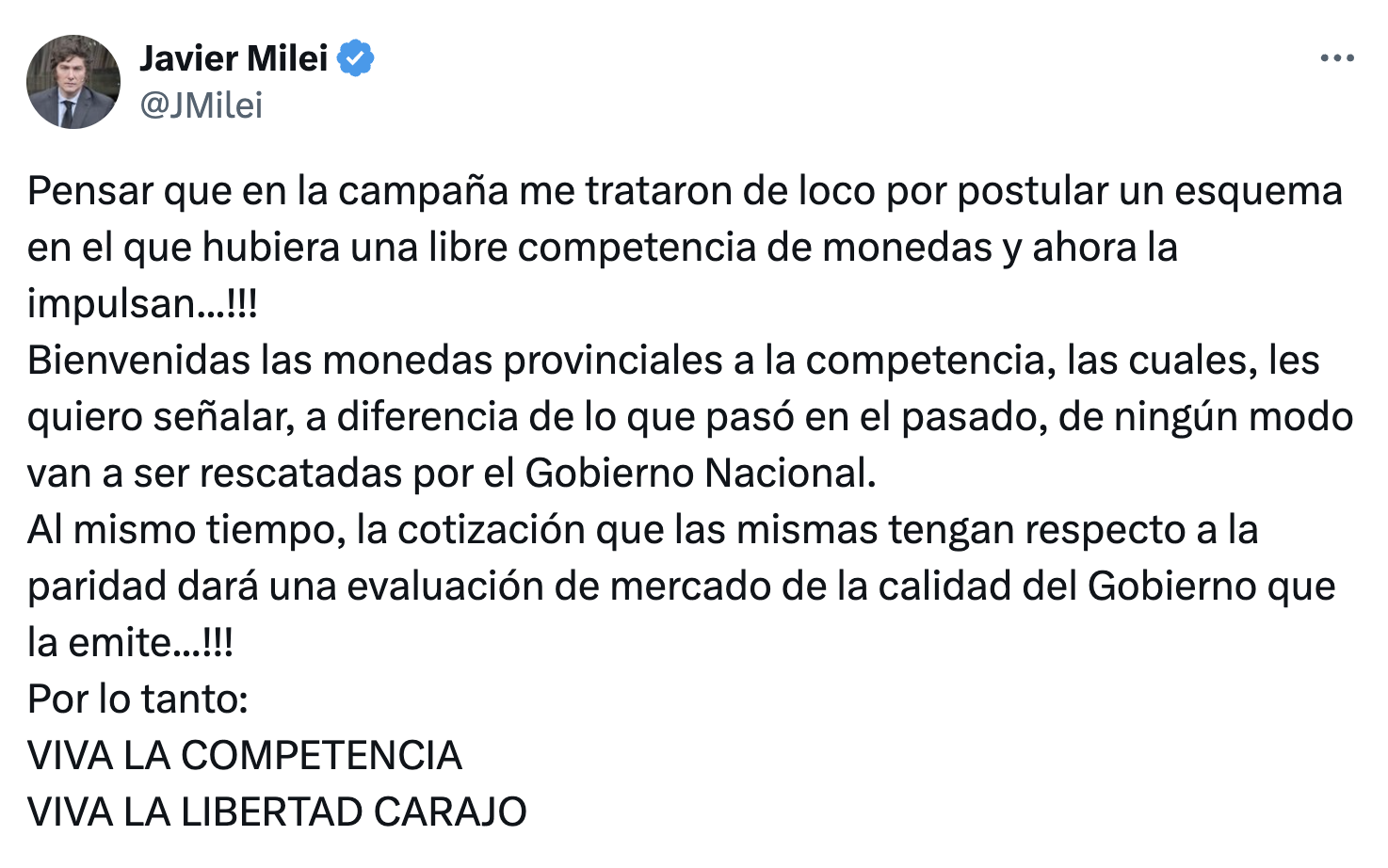

Argentina's new president recently cut off distributions to the provinces. Many of them have a peso deficit: they collect fewer pesos in taxes than they spend. To cover the gap, La Rioja province approved Bocade, a pseudo-currency. They'll pay up to 30% of government salaries. You know what happens next!

But there is a catch: this time the federal government is not willing to eventually print pesos to cover the newly issued Bocade. So, I don't know at what price Bocades will be traded in bakeries throughout La Rioja given that the federal government is not "backing them".

What this means for Argentina's dollarization

By walking through the pseudo-currency timeline, you can see what were to happen as Argentina starts a dollarization process. Re-read the above but this time replace:

- peso → dollar

- bond → peso

Very similar dynamics are in place. Some crucial differences:

- Neither the peso nor the dollar was introduced "at once", in the way the pseudo-currency was. Argentinians have been dealing for decades.

- Dollars are way more scarce than pesos. Much more so than pesos vs bonds back in 2002. There may not be enough dollar liquidity in the market to sustain day-to-day transactions in dollars4. There is enough liquidity for big transactions (e.g. expensive cars and houses) to be done in dollars.

- Dollars can't be printed in Argentina. They have to be borrowed or earned through trade.

Greenback dollars from 1860

Before you laugh this off as something that happens in funny countries like Argentina, consider the greenback dollar, introduced in 1860, and in many ways influenced the dollar that we use today. From the Wikipedia5 article:

Before the Civil War, the United States used gold and silver coins as its official currency.

The first measure to finance the war occurred in July 1861, when Congress authorized $50,000,000 (~$1.29 billion in 2022) in Demand Notes. They bore no interest but could be redeemed for specie "on demand."

Demand Notes were used to pay for soldiers (aka government workers) and were a "pseudo-currency".

Why couldn't the government pay soldiers with regular dollars? Because those were backed by gold and the government didn't have enough gold. Much like Argentina's La Rioja who doesn't have the authority to print pesos, the US government doesn't have the power to create gold. Pseudo-currencies appear when the current real currency is missing.

Not much later:

On February 25, 1862, Congress passed the first Legal Tender Act, which authorized the issuance of $150 million (~$3.44 billion in 2022) in United States Notes.

Since the reverse of the notes was printed with green ink, they were called "greenbacks" by the public and considered to be equivalent to the Demand Notes, which were already known as such. The United States Notes were issued by the United States to pay for labor and goods.

Now we have a second pseudo-currency which people already understand because it is like the previous one.

The bakers didn't like this pseudo-currency:

California and Oregon defied the Legal Tender Act. Gold was more available on the West Coast, and merchants in those states did not want to accept U.S. Notes at face value. They blacklisted people who tried to use them at face value. California banks would not accept greenbacks for deposit, and the state would not accept them for payment of taxes. Both states ruled that greenbacks were a violation of their state constitutions

This new pseudo-currency was traded against the old "real" currency, gold, in the open market:

As the government issued hundreds of millions in greenbacks, their value against gold declined.

In 1862, the greenback declined against gold until by December, gold had become at a 29% premium.

By spring of 1863, the greenback declined further, to 152 against 100 dollars in gold. The greenback's low point came in July that year, with 258 greenbacks equal to 100 gold.

Eventually, the greenbacks were phased out:

The greenbacks rose in value until December 1878, when they became on par with gold. Greenbacks then became freely convertible into gold.

Conclusion?

By following the history of these pseudo-currencies you can see that they are not that much different than "real" currencies. In fact, there is no difference, except that people prefer one currency, so we call the other one "pseudo".

You can also see how currencies "become valuable" as soon as a big enough actor (a) issues enough of it and (b) gives it enough use to be accepted as payment in certain places. This actor doesn't need to be the federal government – it could be a state, a bank, or even a private company.

Thank you to Devon Zuegel for the discussions that led to this post. Thank you Grant Slatton and Willy Chertman for reading early drafts and providing feedback.

Footnotes

- This ARS 1:1 USD peg was called Convertibilidad and lasted 11 years.↩

- This is where Modern Monetary Theory gets the idea that the value of fiat currencies comes from your ability to pay taxes with it.↩

- I couldn't find any pictures in the internet of these signs but I remember them very well. If you have any, please send them to sbensu@gmail.com↩

- I don't know how to estimate this but I am very interested. If you do, please out to sbensu@gmail.com↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenback_(1860s_money)↩